Upper Fort Garry and local government

In the 19th century, Upper Fort Garry influenced the development of political, economic and social life in the Northwest, symbolizing the company’s authority in Western Canada, and more specifically its role in governance in the Red River settlement.

Aside from its commercial importance, Upper Fort Garry was also the seat of civil and judicial authority in Red River. Governance in Red River, a multicultural settlement of First Nations, Metis, and Euro-Canadian settlers, reflected the attitudes of an exclusive and recognizable governing class. This class was largely synonymous with the leaders of the HBC who governed through the Council of Assiniboia. This government was made up of company officers, local clergy, and ‘leading settlers’, all appointed by the company and all, more or less, acting in its interest. The Council had legislative, administrative, and judicial authority in the settlement. It attempted to enforce both the company monopoly on trade and a legal system that included a judiciary made up of magistrates and the General Quarterly Court, a police force, and jail.

The Council convened semi-regularly at Upper Fort Garry but grew increasingly out of touch with many of the inhabitants of Red River, most particularly the growing population of English-and French-speaking Metis who had forged a unique economy based upon agriculture, hunting, freighting, provisioning, and trading. However, as Red River opened to the outside world in the late 1850s, the Settlement was altered again by the arrival of annexationists determined to extend Canada’s control over the western hinterland. The Canadian Party, through its weekly newspaper, the Nor’Wester, was the most vocal in opposition to the HBC and the Metis in Red River. Ultimately, during the attempts to transfer Rupert’s Land to Canada in 1869 the Metis struggle for recognition of their traditional political and land rights led to resistance. Under the leadership of Louis Riel the French and Michif-speaking Metis occupied Upper Fort Garry in November of 1869. It was here that Riel met with Donald Smith, a delegate of the Government of Canada to debate the future of the colony and indeed the whole of the Northwest. Riel’s decision to work with a representative assembly (first a group of 40, then a group of 24) ensured that peace and relative unity would prevail in Red River. When he permitted the execution of an unruly Canadian prisoner, Thomas Scott, in March of 1870, he introduced a flashpoint in Ontario politics but the debate did not disrupt affairs in Red River. The English-speaking Metis of the settlement sat with their French-speaking counterparts in the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia and, acting as responsible representatives of the community, the body voted unanimously to accept Canada’s Manitoba Act and to enter Confederation as the first new province. Later in the summer, Riel was forced to flee the settlement ahead of the arrival of Col. Garnet Wolseley’s troops.

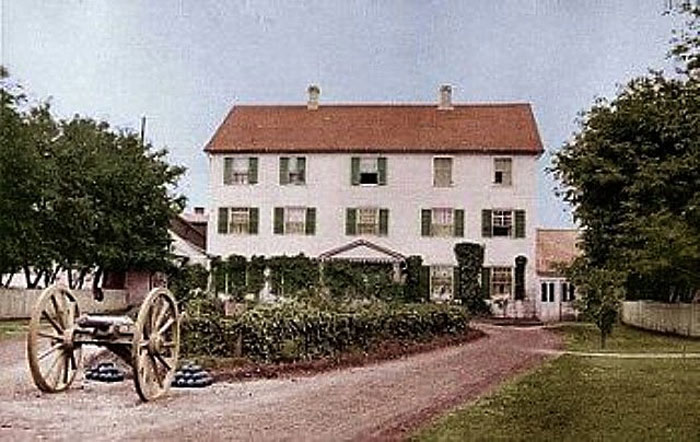

Upper Fort Garry remained the location of Government House and the residence of the province’s Lieutenant Governors until 1883.

The decision by the residents of Red River to enter the new dominion facilitated the consolidation of the rest of northwestern America, including the western interior (1870), and British Columbia (1871), as well as the Arctic (1880), into a single transcontinental nation.

The Fort

As the centre of official trade and civil government in the region for approximately five decades, Upper Fort Garry came to symbolize the authority of the HBC in the Northwest. It then became the headquarters of the Provisional Government, and then, for a time, the administrative centre of the new province. Begun in 1835, and expanded in 1851, the new fort reflected the company’s desire to represent its power and prestige in Rupert’s Land. The limestone walls of the first section were fourteen feet high and incorporated four large stone bastions. Interior buildings — the fur and provision warehouses, the sales shop, as well as quarters for the officers, the men, and the home of the Chief Recorder — followed a basic ‘H’ configuration common to other HBC wooden palisaded posts and reminiscent of the Great Hall model of castle construction in the early Middle Ages. (Other buildings such as the courthouse, jail, some workshops, and a stable were located outside the walls.) Limestone construction provided the company with a defense against a lightly armed and mounted enemy and served as protection against devastating floods and prairie fires. Perhaps more importantly, limestone walls and bastions helped to reinforce the HBC’s power and authority in the region. However, as the company’s influence waned in the latter half of the 19th century, these stone symbols of dominance were dismantled.

From Upper Fort Garry grew the roots of a new commerce, a challenge to the HBC monopoly in the old settlement and later, the development of Winnipeg and a burgeoning economy of supply, manufacture, and transport.